Pet Shop Boys keyboardist Chris Lowe talks about the band’s new album, Yes

Almost 25 years ago, the Pet Shop Boys launched their career with this striking couplet: Sometimes youre better off dead / Theres a gun in your hand and its pointed at your head. Not exactly a conventional chart-topping lyric, but then Neil Tennant and Chris Lowe have never gone in for pop platitudes.

On that first hit, West End Girls, and albums such as Please, Actually and Introspective, the English duo offered scathing social commentary about Thatchers Britain. PSB songs were populated with rent boys, get-rich-quick artists and bored suburban kids, all scrambling to survive in the greed is good decade.

While other synth duos from that era have gone to that great electronics store in the sky (R.I.P. Eurythmics and Yazoo), Tennant and Lowe continue to stretch the boundaries of pop, collaborating with architects, opera designers, even co-writing a ballet (which is due to launch in 2011). On the 1988 track Left to My Own Devices, Tennant described their aesthetic as Che Guevera and Debussy to a disco beat as good a summary as any of the Pet Shop Boys singular style. The duo recently received a lifetime achievement award at the Brits, joining some pretty exclusively company (David Bowie, The Who and Elton John, among others).

Their tenth studio album, Yes, will be released on March 23. Over the phone from London, keyboard wizard and founding pet shop denizen Chris Lowe spoke to CBCNews.ca about the financial meltdown, why MTV Cribs is repulsive and how talent shows such as Pop Idol have ruined Christmas for him.

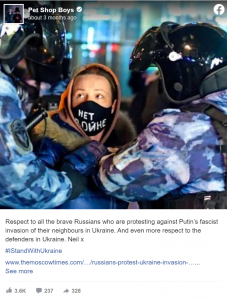

Q: Your last album, Fundamental, was very political, with several references to the war on terror. The song Integral was critical of Britains plans for a national identity card, and you slammed Tony Blair and George W. Bush on Im With Stupid. The new album seems much more hopeful.

A: We had lots of points to make on the last album. I dont know what the situations like in Canada, but in England now, there are CCTV cameras everywhere you go. Theyve brought in lots of anti-terror laws which curb human rights and civil liberties; there was a lot to talk about. But I think we probably said it all in that album, and we probably just felt freer to have fun and write more joyous pop songs on this one.

Q: Is that why you chose Yes as the album title?

A: I think the reason we chose this album title was because its a very positive, uplifting-sounding album. Theres a lot of hope in there, and musically its very positive, uplifting, a very shiny pop record. And in that sense its like our album Very. Its that sort of album title, which expresses the sentiments and feelings of the music contained within it.

Q: Your new single, Love Etc., has anti-materialistic lyrics that seem especially timely: You need more/Than the Gerhard Richter hangin on your wall/A chauffeur-driven limousine on call/To drive your wife and lover to a white tie ball/You need more. What inspired that song?

A: Well, the song was co-written with Xenomania, the producers of the album. Neil wrote the lyrics, but unlike on the last album where we actually almost had a manifesto of what we wanted it to be about this time, we just wrote a lot of songs and they ended up being rather good pop songs. I think theres a general theme of love on the album. But also I think it was inevitable that there was going to be some financial collapse, because there was just so much greed and selfishness out there with all the city bonuses and all the rest of it, being constantly being bombarded on television with images of wealth, particularly on MTV Cribs and stuff like that. I think its just really distasteful and vulgar and ends up leading to a horrible, must-have culture, and so this might have been subconscious, really; I think it definitely was a reaction against the materialism of the recent years.

Q: You and Neil are writing a ballet based on a story by Hans Christian Andersen. How did that come about?

A: We have a friend who is principal dancer at the Royal Ballet in London. He got in touch with Neil and asked whether the Pet Shop Boys would be interested in writing some music for him to perform to at Sadlers Wells. I didnt know about that, but Id recently purchased a new translation of the stories of Hans Christian Andersen. I read one of them one night and thought wow, thatd make a really good ballet. So I phoned Neil up the next day and said Id read this really great story thatd make a fantastic ballet; Neil said, Thats really strange, because weve just been offered one. We thought that was fate, so we decided to go ahead with it. Weve written a third of the music now, workshopped a couple of scenes and got the go-ahead for it. Now weve basically just got to find the time to write the rest of the music, because its quite a big project. I think what our friend was probably expecting was some electronic music that he could do some contemporary dance to, but what hes actually getting is more of an old-fashioned storytelling ballet like Tchaikovsky would do. Its a very ambitious project involving quite a cast, set design, orchestra quite a big production.

Q: A recent article in The Guardian said that the Pet Shop Boys merge pop and art perfectly and compared what you guys have done in this regard to The Beatles. There arent many bands whove collaborated both with pop groups like Girls Aloud and experimental filmmakers like Derek Jarman

A: No, there probably arent. Well, we love collaboration, we love bringing people into our world, into the world of pop. Not many people work with architects, but Zaha Hadid did set designs for us [on the 1999/2000 world tour]. I think it makes the whole thing more interesting, because pop music is a visual art as well as being about music, and looking at different ways to present yourself is always very exciting. We genuinely love pop music, which is why were interested in Girls Aloud, but we also like independent film and we also like fashion. So its just interesting to bring all those elements together, to see what happens. We always try to do things differently from anyone else, we try to be unique. You cant really reinvent the wheel but we do try to bring other elements into pop music; we always try to work with architects, artists, opera designers.

Q: Neil recently gave an interview where he was critical of shows like Pop Idol and the range of music they present. Do you agree with him? What do you think of the state of pop today?

A: Well, it depends how you define pop music, because we think that the Arctic Monkeys and MGMT are pop music. So it all depends how you define it. [The Idol shows] have a very narrow view of pop music; its hardly all encompassing. Theyre generally looking for someone who can sing a bit like Mariah Carey. I think its great that people are given the opportunity to have success in a way they might not have previously done, but I think it was in Spain where eight of the top ten albums were all from Spain Idol or whatever they call it and it can clog it all up a bit. For instance, the race for the Christmas No. 1 was always very exciting in England. It was like, wow, whos going to be No. 1 at Christmas? But of course now we all know whats going to be No. 1 at Christmas a big ballad written by the winner of Pop Idol or X Factor.

Everything is so formulaic, there are no surprises anymore. Its not really what we think of as pop music. Coming up in the 80s, what was great was that it was all people who didnt really know what they were doing! People learning their way around a recording studio, learning how to use synthesizers and realizing that they could make pop songs. There was a lot of experimentation and a learning process going on in the making of pop music in the 80s, and I think the Pop Idol songs do stifle that somewhat.

Q: Have you noticed over the years that pop seems to be a dirtier word in North America than it is in Europe?

A: Well, a dirtier word than pop in North America is disco, which we called one of our dance albums. We dont make life easy for ourselves we should probably call ourselves an indie rock act, or electronica might be better. A good song is a good song and pop music, I always feel, is the music that you remember; its the music that lives on. Theres been lots of rock music thats been very popular in its day and isnt really remembered at all now whereas the hits of Motown are going to live forever, arent they? I dont think those were highly regarded [critically] at the time. You cant really beat the euphoria of a perfect pop song.

Taken from: CBCnews.ca

Interviewer: Greig Dymond